Migration to Europe – State of play

Migration is a complex and global issue that affects not only countries of departure, transit and arrival, but mainly the human beings involved in the entire process. Migration has always been part of the human nature. Just consider that in 2013, 232 million of international migrants, together with 740 million of internal migrants, accounted for almost 1 billion, out of 7 billion of the world population. 1 out of 7 world inhabitants was a migrant.

In recent years, migration has assumed kind of a negative connotation, being described as a threat to European security and stability. It has occupied newspapers’ front pages and headlines on the wake of an unprecedented crisis that hit the Old Continent, which did not experience such a flow of immigrants since the Second World War. How to answer the call for help launched by thousands of people coming from countries beset by war, generalised violence, or repressive governments? How to coordinate the opinions and the responses of multiple countries and actors? How to guarantee security and stability, without undermining people’s rights? How to stay human?

By now, not only political elite, but also public opinion, have focused more on the consequences, than on the causes. The migrant crisis is the brutal consequence of many causes. By changing the perspective, we should talk about the crisis of the European regulatory framework on international migration and on asylum; about the crisis of the European security and intelligence system, still too fragmented and unable to tackle the instead efficient smugglers’ network; about the crisis of the European values. It is clearly a complex and delicate matter, as by now we have been seeing just the tip of a very large iceberg. To formulate more sustainable and long term strategies, a brighter light needs to be shed on the causes.

Starting from a brief examination of this critical framework where human rights’ protection and EU traditional values and reputation are at stake, this analysis aims at investigating illegal immigration in Europe, by focusing first on the role played by the existing European legal measures regulating migration, secondly on the key function human smugglers and transnational organised crime have in this inhuman game.

Before doing that, let us consider some key definitions to facilitate further understanding.

First of all, migration, as defined by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) is “the movement of a person or a group of persons, either across an international border, or within a State. It is a population movement, encompassing any kind of movement of people, whatever its length, composition and causes; it includes migration of refugees, displaced persons, economic migrants, and persons moving for other purposes, including family reunification.” As confirmed by this definition, migration is a multifaceted phenomenon, as many differences exist between persons’ legal status (asylum seeker, refugee, internally displaced person stateless person), the length of their stay, the causes of the movement – forced migration, voluntary migration, labour migration, circular migration, irregular migration. Moreover, the same flow of migration could include refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants, but also particularly vulnerable people, victim of trafficking, subjected to violence or trauma, or unaccompanied minors. In this case, we talk about “mixed flows of migrations”. All persons, irrespective of their immigration status, are covered by human rights instruments, but refugees have a distinct legal status under the 1951 UN Convention relating to the status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol.

“Irregular migration” is the movement that takes place outside the regulations of the sending, transit and receiving countries. For the sending or the transit country, the irregularity takes the form of an international boundary’s crossing without a valid passport or travel document; from the perspective of destination countries, an irregular migrant is the one who entries, stays or works without the necessary authorisation or documents required under the country’s immigration regulations.

“Illegal migration” refers to cases of smuggling of migrants and trafficking in persons, and combines the violation of national and/or transnational regulations disciplining people’s movements with the – usual –infringement of human rights.

Smuggling, as described by the UN, is “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident.” Smuggling, contrary to trafficking, does not require, but often presents, an element of exploitation, coercion, or violation of human rights.

The Council of the EU in the Directives 2002/90 and 2011/36 discerns “smuggling of migrants (facilitation of irregular migration)” from “human trafficking” stating that the former means “intentionally assisting a person who is not a national of a MS, for financial gain, to reside within the territory of a MS in breach of the laws of the State concerned on the residence of aliens,” whereas the second corresponds to “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or reception of persons, including the exchange or transfer of control over those persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.”

Recent Trends

Countries of first arrival to Europe

| Country | Arrivals | Percentage Change |

|

| Previous week

30 June – 06 July |

Current week

07 July – 14 July |

||

| Italy | 6,297 | 3,014 | -52% |

| Greece | 216 | 351 | -62% |

| Bulgaria | 720 | -100% | |

| Sum of arrivals | 7,233 | 3,365 | -53% |

Source: IOM

From 1998 till 2013, 623,118 migrants have tried to reach the sea shores of the EU, representing an average of almost 40,000 persons a year (De Bruycker, Di Bartolomeo, Fargues, 2013). In recent years, numbers have been increasing drastically, mainly due to the progressive deterioration of the political situation in the Middle East, Africa and Central ASia – Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Somalia. 1,011,712 arrivals occurred in Europe in 2015. 249,531 people arrived in Europe in 2016, by now, 240,323 by sea and 9,298 by land (Statistics from http://migration.iom.int/europe/). 2,933 people have been recorded as dead or missing in the Mediterranean, in the same period. On top of this, there are those migrants who lost their lives also in other stages of their journey, because of starvation, dehydration, or even imprisonment and torture. Between 1996 and 2011 at least 1,691 people died while attempting desert journeys.

European regulations and human smuggling

Considering that 90% of irregular migrants to Europe are able to embark into a journey thanks to the services provided by smugglers, it is important to understand why they need to resort to this unpleasant solution to reach the European external borders.

Article 26 of the Schengen Convention affirms that “(a) If aliens are refused entry into the territory of one of the Contracting Parties, the carrier which brought them to the external border by air, sea or land shall be obliged immediately to assume responsibility for them again. […] (b) The carrier shall be obliged to take all the necessary measures to ensure that an alien carried by air or sea is in possession of the travel documents required for entry into the territories of the Contracting Parties.” As a consequence, migrants without a visa are not allowed on aircrafts, boats or trains going into the Schengen Area; this explains why migrants without a visa often resort to migrant smugglers.

Furthermore, under the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), a prerequisite for seeking asylum is that the potential asylum seeker arrives on the territory of a Member State, including at the border or in the transit zones of that Member State. As EU law does not provide for ways to facilitate the arrival of asylum seekers, and as migrants are often from countries that do not have automatic visa agreements, or who would not otherwise qualify for a visa, they often cross the borders illegally.

As demand and supply interact on the market of goods and services, in the same way demand and supply of a way to reach the European external borders interacted in this specific historical moment, and criminal networks quickly adapted to this development, by increasing their involvement in migrant smuggling.

As it is a clandestine crime of a hidden nature, it is hard to collect reliable and verified information and statistics.

However, both the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and Europol have been studying the phenomenon and have collected important findings. In 2015, the turnover from migrant smuggling was estimated between EUR 3 and 6 billion. This may double or triple if the scale of the current migration flow persists in the upcoming year. Some 55,000 migrants are thought to be smuggled from East, North and West Africa into Europe every year, generating around EUR 170 million in revenue for criminals. The fees charged to smuggle migrants differ substantially on the basis of the point of origin, with figures ranging from $2,000 to $10,000. They also offer several facilitation services such as the provision of transportation, accommodation and fraudulent documents at very high prices. In many cases, irregular migrants are forced to pay for these services by means of illegal labour.

According to Europol, this machine successfully works thanks to a systematic chain, made up of: network and local leaders, who respectively coordinate the activities during the whole route and in a specific part of the segment; a counterfeit documents’ provider; a broker who gets in touch with the migrants to arrange the travel and the provision of documents; facilitators who help with the travel’s logistics, i.e. boat crew, driver, translator; legal businesses, like hotels, travel agencies and car rental, that are used as support to the entire process; a trustful money handler; last but not least corrupt officials. Smugglers’ profiles may vary: full-time professional criminals are involved in smuggling migrants around the world, but there are also those who combine this criminal activity, with other ones like drug or human trafficking. There are also many smugglers who run legitimate businesses and are involved in the smuggling of migrants as opportunistic carriers or hospitality providers who choose to look the other way in order to make some extra money.

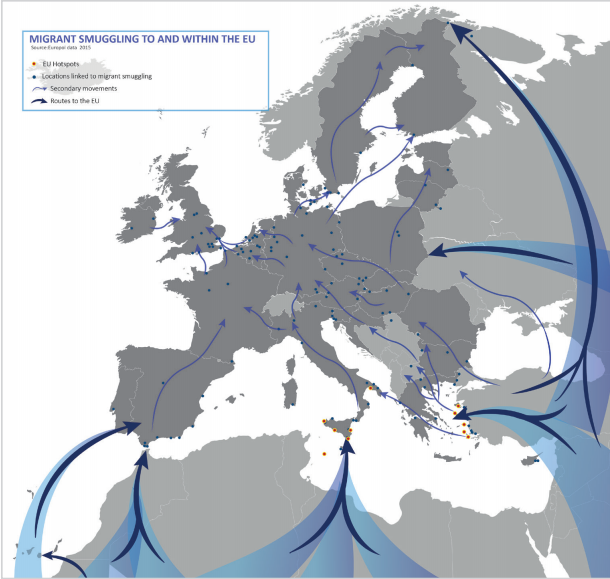

A migrant’s journey takes them from their country of origin through a number of transit countries to their eventual country of destination. Along the routes crossing the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas ,Turkey and Libya are the main transit countries before reaching the EU – Greece and Italy. The latter could also be transit countries, before the migrants reach their final destination – i.e. Germany, Sweden, UK. Smuggling hotspots are located along the main migration routes and attract migrant smuggling networks. Migrant smuggling is an international criminal business. The suspects reported to and identified by Europol originate from more than 100 countries. The most common nationalities or countries of birth for these suspect are Bulgaria, Egypt, Hungary, Iraq, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey.

The journeys feature different levels of safety, according to the amount of money paid. The majority of male and female respondents interviews by the IOM (2016) reported estimated cost of their journey from 1,000 to 5,000 USD (78% and 79%, respectively). Women comprise a larger proportion of individuals (13%) paying more than 5,000 USD per person on the journey, compared to men (9%). Migrants with little financial means take a “pay-as-you-go” package in which they pay separately for different parts of the journey to smugglers who may not be part of the same network. Instead, the “package deals” are quicker, safer and have a higher guarantee of success, but also more expensive.

Smuggled migrants could also be subject to merciless human rights abuses, and the journey can turn into a real torture: people might be squeezed into exceptionally small spaces in trucks or boats in order for smugglers to maximize their profit. Migrants might be also raped or beaten en route or left to die in the desert. The migrants smuggling and related activities put in danger many people’s lives and generate billions of dollars in illegal profit. They also fuel corruption and enhance the ties of the transnational organised crime network. Intercepting and combating this crime is then fundamental.

Countering migrant smuggling

Both the European and international bodies have set up regulatory systems to counter and undermine the functioning of the smuggling criminal network.

The 2005 EU Global Approach to Migration and Mobility (GAMM) has, among its main priorities, to better organise legal migration, and foster well-managed mobility; to prevent and combat irregular migration, and eradicate trafficking in human beings; to maximise the development impact of migration and mobility; to promote international protection, and enhancing the external dimension of asylum. The Council Facilitation Directive (2002/90/EC) defines unauthorised entry, transit and residence, and provides for sanctions against those who facilitate such violations. This Directive requires that every MS adopt appropriate sanctions on all persons who intentionally assist – instigate, participate or attempt to assist – non-nationals of the MS to enter, transit through or reside in the territory of the MS. According to the “humanitarian clause”, included in Article 1(2) of the Directive, the MS may decide not to impose any sanctions in cases where, if formally the aim of the behaviour is to assist migrants to transit or reside in a territory where is not legally allowed, substantially, they provide humanitarian assistance to the person concerned – for example, NGOs assisting the migrants in transit in areas such as Calais or the Serbian-Croatian border, with emergency shelter, legal aid, etc.

In connection to the latter, the Council Framework Decision 2002/946/JHA set the penal framework to prevent the facilitation of unauthorised entry, transit and residence., and requires that the MS take measures that would punish illegal migration. The criminal penalties can be accompanied by confiscation of the means of transport used to commit the offence. Acts committed for financial gain should be punished by custodial services.

UN Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, adopted by the UN, and approved by Council Decision 2006/616 and by Council Decision 2006/617, obliges the parties to consider certain acts as criminal offences when they are committed intentionally in order to obtain a financial or material benefit. These acts include migrant smuggling, producing fraudulent travel or identity documents, or enabling migrants to remain in a country without complying with the necessary requirements. Endangering migrants’ lives or treating them inhumanely are considered aggravating circumstances. Countries should not prosecute migrants but only those facilitating their entry or stay.

The European Commission is also tackling smuggling through various policies. Among the short-term priorities of the European Agenda on Migration there are saving lives at sea and tackling criminal smuggling networks. In the EU Action Plan against migrant smuggling (2015-2020) (COM(2015) 285), the Commission noted that it would ensure that appropriate criminal sanctions are in place while avoiding the risks of criminalising those who provide humanitarian assistance to migrants in distress. The European Action Plan against Migrant Smuggling planned to revise smuggling legislation, destroying smuggler vessels and stepping up the seizure and recovery of criminal assets. Other actions included strengthening the JOT MARE operation, developing guidance on migrant smuggling and strengthening bilateral and regional cooperation frameworks and financial support for non-EU countries to tackle smuggling in their territories.

In 2015, the EU Council also launched a European Union Military operation in the Southern Central Mediterranean – EUNAVFOR MED, now renamed Operation Sophia. The operation aims at identifying, capturing and disposing of vessels, as well as enabling confiscation of assets used or suspected of being used by migrant smugglers or traffickers, in order to contribute to wider EU efforts to disrupt the smuggling networks in the Southern Central Mediterranean and prevent the further loss of life at sea. Last 20 June 2016, the Council extended until 27 July 2017 Operation Sophia’s mandate reinforcing it by adding the duty of first, training of the Libyan coastguards and navy; secondly, of contributing to the implementation of the UN arms embargo on the high seas off the coast of Libya.

The operation focuses on smugglers rather than on the rescue of the migrants themselves, even though actions to prevent further loss of life at sea are a visible part of the mandate. The objective is less to stop migration flows than to disrupt smuggling routes and capabilities and, hence, reduce the flows originating from the Libyan coast, which has been (together with the eastern route) the main point of departure.

NATO is also playing a role at sea, by deploying its ships, in close consultation and coordination with both Greece and Turkey. NATO highlights that “the purpose of [the] deployment is not to stop or push back migrant boats, but to help our Allies Greece and Turkey, as well as the European Union, in their efforts to tackle human trafficking and the criminal networks that are fueling this crisis.

What more?

The outlined regulatory framework makes the EU and neighboring countries committed in the effort to transform the smuggling from a low risk-high revenue business, to a high risk-low revenue one. Although, there are many doubts on whether these norms will serve their purpose, through actions of punishment, deterrence, intimidation and coercion. It has been demonstrated that people who want to escape from war, persecution and death will find a way to do so: diversification of routes and creation of new hotspots, are always on the agenda, as there is the demand for facilitation services. As a matter of fact, after many deaths in the Mediterranean Sea, many more people decided to abandon the sea route for the land one – Western Balkan route.

In addition to this, the operation’s mandate of tackling the smugglers does not resolve the question of the migrants, of their destiny and the protection of their rights as human beings, and prerogatives as potential asylum seekers. Therefore, more attention should be placed on to the mixed flows of migration and the refugees’ and human rights responsibilities of the Member States, as outlined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, the Refugee Convention and the European Charter of Human Rights (ECHR). These are extraterritorial measures, implemented regardless of MSs territory and regardless of where institutions and bodies are placed. EU institutions and MSs are failing to guaranteeing extra-territorial protection of migrants’ rights, as no legal mechanisms and/or route exist to facilitate entry into the EU. Among the tools the EU may use to answer its duty of safeguarding human rights, there are the “humanitarian visas,” which could allow a non-national to approach the potential host state outside its territory with a claim for asylum or other form of international protection. The Schengen acquis and the common EU visa policy discipline something similar to this, when providing the legal basis for the MSs to issue national long-stay visas, as well as short-stay visas with limited territorial validity (LTV) on humanitarian grounds, for reasons of national interest or because of international obligations.

Apart from these the specific tools (humanitarian admission, temporary protection, diplomatic asylum, extraterritorial processing of asylum applications, humanitarian evacuation, resettlement and regional protection programmes, among others) that may be used by the EU to address migrants’ prerogatives, a comprehensive, multi-dimensional response, which begins with addressing the socio-economic root causes of irregular migration is needed. A closer international cooperation, as well as more solidarity and responsibility-sharing are necessary not only to investigate and disrupt the smugglers’ network, but also to assist the migrants.

Giulia Formichetti

Master’s degree in International Relations (LUISS “Guido Carli”)

References

Philippe De Bruycker, Anna Di Bartolomeo, Philippe Fargues, (2013, September) “Migrants smuggled by sea to the EU: facts, laws and policy options”, Migration Policy Centre (MPC), RSCAS, European University Institute (EUI, Florence) MIGRATION POLICY CENTRE (MPC) RESEARCH REPORT.

Council of the EU (2016) EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia: mandate extended by one year, two new tasks added (Press Statement), June 20. Retrieved from bit.ly/2acxVC0.

European Commission, DG HOME (2014), A Common European Asylum System, http://bit.ly/162mAiW.

European Commission, DG HOME (2015, September) A study on smuggling of migrants: Characteristics, responses and cooperation with third countries, Final Report.

Europol Public Information (2016, February), Migrant smuggling in the EU.

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2013), Handbook on European law relating to asylum, borders and immigration, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, para. 1.6.

Ulla Iben Jensen (2014) Humanitarian visas: Option or Obligations?, European Parliament.

IOM (2009, October 19), Irregular migration and mixed flows: IOM’s approach, MC/INF/297, International Organisation for Migration, paras. 3 and 4, cf. para. 5.

IOM (2011), Glossary on Migration, International Migration Law Series No. 25.

IOM (2016), Mixed Migration Flows in the Mediterranean and Beyond, Analysis: Flow monitoring surveys reporting period October 9 – July 11.

NATO (2016, March 06), NATO Secretary General welcomes expansion of NATO deployment in the Aegean Sea.

Thierry Tardy (2015, September) Operation Sophia Tackling the refugee crisis with military means, EUISS

United Nations (2000)UN Protocol Against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime.

UNODC, Smuggling of migrants: the harsh search for a better life, retrieved from http://bit.ly/1PlWq9x.