What if Israel assertively breaks into the gas market as a reliable exporter for the European Union? As it has previously been discussed[1], the discovery of the Tamar (2009) and Leviathan (2010) gas fields put Israel in an unpredicted position, making it able to exploit a huge amount of resources (24.4 trillion cubic feet[2] combined), both for its internal market and for export. While the Tamar field is already pumping energy to Israel, developments on the Leviathan field have been repeatedly delayed due to regulatory issues and the intervention of the antitrust authority.

A reliable gas provider: a new pipeline for many beneficiaries

However, the plans to draw a new energy infrastructure landscape within the Mediterranean Sea are now moving forward. During a meeting held last month in Tel Aviv, Israel displayed its “ambition to become an exporter of energy to Europe, signing a preliminary agreement with Cyprus, Greece and Italy to pump natural gas across the Mediterranean”[3] via a pipeline. This agreement, reached by the Energy Ministries of the four countries involved, has been signed with the endorsement of Miguel Arias Cañete, the EU’s Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy. The project, in fact, would contribute to the Union’s primary strategy to diversify sources and suppliers, and would be eligible to receive funding via the EU’s Connecting Europe Facility, a programme that supports the development of trans-European infrastructure.

The proposed project would link Israeli and Cypriot offshore gasfields (Leviathan and Aphrodite) to Greece and Italy for approximately 2,200 km, becoming the world’s longest and deepest (up to 3 km depths) pipeline. Estimates led by Israel’s Energy Ministry say the project could be completed by 2025 with an expense between 6 and 7 billion dollars.

During the joint event for the presentation of the pipeline, Yuval Steinitz, Israel’s Minister of Energy, tried to strike the audience by talking about a real possibility to export 3,000 bcm of gas. An option particularly attractive for his counterparts like Carlo Calenda, Italy’s Minister of Energy, who said the project is a priority for his country in terms of transition from the use of coal[4]. His Greek homologous, Stathakis, went far beyond describing Israel as “the most reliable export option”. As a matter of fact, the southern route has undoubtedly been considered fundamental by north Mediterranean countries for years within the strategy to reduce their energy dependency from the Russian Federation. Furthermore, a possible extension to western European countries or towards the Balkans is still considered as a possibility.

The discovery of the Leviathan gas field really projected Israel in a new dimension. Jerusalem is gambling its chances to become a regional energy exporter and, after the signing of contracts for gas distribution to Jordan and Egypt (another gas hub wannabe after Zohr gas field’s discovery), it made efforts to create a market as broad as possible for its reserves. That is why, trying to use them as a political tool, during the last months a hesitant reconciliation with Turkey occurred[5]. Both countries resulted eager to exploit the energy find, and Turkey in particular desires to diversify its energy imports and resources. In this perspective, talks for an undersea gas pipeline with Turkey began. However, the proposed route would run through Cypriot territorial waters, thus the political environment would make the project hardly feasible.

After all, almost two years ago, Netanyahu sincerely admitted to consider gas supply as a foundation of national security because exports make Israel crucial for other countries. Netanyahu explained his manifesto by saying: “The ability to export gas makes us more immune to international pressure. We don’t want to be vulnerable to boycotts” . In other words, Israel is likely to implement the same doctrine conceived in Moscow. It is not a case if some observers, reporting about the proposed pipeline, also talked about a project to compete with Russia[6].

A rogue path

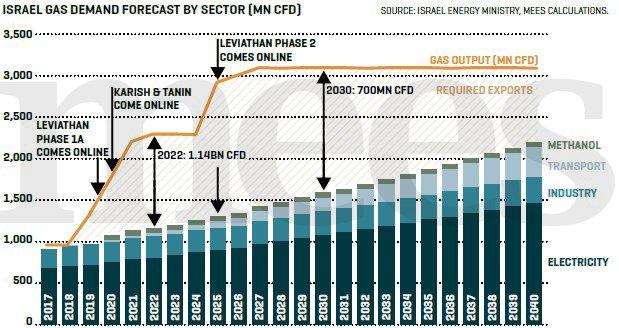

Skepticism is really surrounding the pipeline towards Italy for both economic and political reasons. “The implementation of such projects sometimes takes decades. There is also a need to establish more proven reserves” said Amit Mor, from a consulting firm. In other words, keeping to supply the internal market or closer countries would not represent such a risky gamble and could bring secure benefits in the short run. Furthermore, it cannot be taken for granted that political goals perfectly correspond to investment decisions by companies for two reasons: it is not certain that current gas demand trends in southern Europe commercially justify an additional new gas supply project[7]; and it is not possible to isolate the project from the regional political framework. The first one is a problem pointed out by several observers like MEES (Weekly Middle East Oil & Gas News an

d Analysis) that sees an alarming surplus of gas with no market for it.

Source: MEES

Source: MEES

Furthermore, the pipeline has come under criticism from Palestinians as the Gaza Strip continues to suffer from a crippling power crisis. Shawan Jabarin, General Director for Al-Haq, an independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organization based in Ramallah, highlighted that the pipeline will benefit the companies which profit from the occupation of the Palestinian territory. According to Jabarin, the pipeline is an “incentive for Israel to continue the closure of Palestine’s coast and a tacit approval by Europe of Israel’s ‘naval blockade’ and continued international armed conflict in the waters off the Gaza Strip”[8]. Susan Power, legal researcher for Al-Haq, denounced that Israel has employed a brutal and unlawful naval operation to protect Noble Energy’s gas platforms beside the Gaza Strip, routinely attacking, killing and injuring civilian Palestinian fishermen who fish in the vicinity of Israel’s illegally imposed six-nautical-mile closure of Palestine’s territorial waters[9]. It seems the countries involved in the project didn’t care about Palestinians’ complaints when signing the deal. In fact, the pipeline serves a number of greater geopolitical objectives, namely immunizing Israel from criticism and sanctions, and damaging relations between Europe and Russia. However, it is also true that these stances can change as the ongoing struggle between Israelis and Palestinians evolves.

Conclusions

Once again, energy reveals the engine behind almost every political readjustment within the Mediterranean basin. Israel’s entrance into the list of gas exporters could completely overturn several national energy strategies and give the EU’s strategy a substantial boost. As highlighted, the pipeline project is in its early stage, vulnerable to multiple “stops-and-goes” as it has occurred to several other pipelines (e.g. South Stream, Turkish Stream). Hence, every forecast today just resembles a speculation. At the moment, meetings between the parties have been planned every six months to allow a progressive update. The completion of the opera by 2025 seems a very ambitious goal considering what happened with similar projects like the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, another infrastructure reaching southern Italy and able to diversify EU gas suppliers. Israel’s ambitions are legitimate, but seem to hardly meet market considerations. Therefore, it still needs to be proven if political reasons will prevail on economic ones.

Francesco Angelone

Master’s degree in International Relations (LUISS “Guido Carli”)

[1] Angelone, Francesco. “It’s the energy, stupid! How oil & gas can reshape the Mediterranean”, Mediterranean Affairs, 29 January 2016. http://mediterraneanaffairs.com/its-the-energy-stupid-how-oil-gas-can-reshape-the-mediterranean/.

[2] Source: Noble Energy.

[3] Reed, John. “Israel signs pipeline deal in push to export gas to Europe”, Financial Times, 3 April 2017. https://www.ft.com/content/78ff60ca-184c-11e7-a53d-df09f373be87.

[4] Yefet, Nati. “Israel-Europe gas pipeline moves ahead”, Globes, 4 April 2017, http://www.globes.co.il/en/article-israel-europe-gas-pipeline-moves-forwards-1001183859.

[5] Deutsche Welle. “Israel and Turkey hope to rekindle relations through natural gas sales”, DW.com, 13 October 2017, http://www.dw.com/en/israel-and-turkey-hope-to-rekindle-relations-through-natural-gas-sales/a-36031314.

[6] Rettman, Andrew. “Israel-EU gas pipeline to compete with Russia”, EUobserver, 4 April 2017, https://euobserver.com/energy/137487.

[7] Gostoli, Ylenia. “Israel-Europe gas deal sparks criticism”, Al Jazeera, 23 April 2017, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/04/israel-europe-gas-deal-sparks-criticism-170411073907336.html.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] Ibidem.